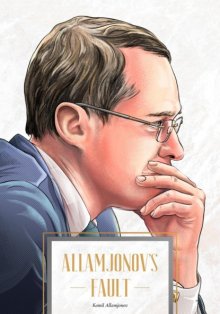

Allamjonov's fault бесплатное чтение

Allamjonov's fault

Komil Allamjonov

Foreword

Why did I write this book?

There are three reasons I might have for writing this book, and two of them simply don't stand up to scrutiny.

The first would be to make money. Well, I don't need any more of that.

The second would be to show the world what a hard-faced renegade I am. But many people both in Uzbekistan and abroad know me well enough that I wouldn't be able to pull the wool over anybody's eyes in that regard.

And then there's a third possible reason: I want to communicate with a certain group of people and tell them something truly important. Those between the ages of fifteen and thirty. Those who are looking at the world and thinking: «What's my next step? How am I meant to live in this ever-changing society? How do I survive? Is there any way for me to become someone important without the support or favour of somebody who's already made it? Who actually needs me and will my dreams ever come true?»

I will tell you about my own journey. What helped me grow up and become the man I am today. I will do my best not to leave anything out.

Until I decided to write this book, I always thought that I was just incredibly lucky. It seemed as if my life had been nothing but uninterrupted success. I mean, as I write, I am sitting here at my desk in my comfortable, warm home with my family; I have a successful business and my work is extremely interesting. Who am I if not Fortune's favoured son?

But when I actually took a moment to look back over my life so far, I realised that things didn't work out for me three or four times more often than they did. There were so many failures for each success that you simply couldn't call it simple luck.

As is well known, my mother was a nurse midwife. Now, midwives don't lead particularly privileged lives, though there is one privilege that they can rely on and that's the ability to give birth to their children at their own workplace, under the care of doctors they trust since, after all, they are all colleagues and friends. But do you know what? When the time came for her to give birth to me, mum's maternity ward, the same one she worked in, was closed for disinfection («cleaning»).

I

The Minister is here

As a little boy, whenever I was crawling under the grown-ups' feet, whining, throwing a tantrum, or just generally up to no good, my grandma always used to say: «Don't reproach the boy, leave him be. He'll be a minister one day».

He'll be a minister one day.

I really don't know where she got that idea from. According to her, none of the other kids in our family were destined to become-ministers, just me. If truth be told, there was absolutely nothing to suggest that I, the modest son of a car mechanic and a nurse, would ever go on to be someone important.

I asked my mum, and she was equally as perplexed as to why grandma thought so.

Yet here I stand, some thirty-odd years later, in the lobby of the UAPI1 building. As a minister. After all, Head of the Uzbek Press and Information Agency is a ministerial position. I'm stood on the first floor of a huge, echoing building with peeling walls, cracked ceilings, crumbling floors, and rubble and debris all around. Not to mention the unshakable stench of raw sewage emanating from my ministerial office. The UAPI building is a Stalinist behemoth. When it was last renovated, no one can say.

The edifice has a total of five hundred individual offices, every last one of which is occupied by someone or other: the Women's Committee, various political parties, assorted print media outlets, and a handful of businesses. The internal courtyard is completely chock-full of cars; people rushing here and there, but nobody pays me any attention at all. Then there's the second floor, with its unimposing left wing: the UAPI itself.

There to introduce me to the team was none other than Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Jamshid Kuchkarov. He did so and then left summarily. A veritably ancient Head of Typography and various department heads of equal seniority were sat at the conference table. Each one of them to the last was recruited back in the Soviet era and had been working in that building for at least half a century. And at that very moment, I could immediately sense their collective reaction. It was exactly as if a little boy had just burst into the room, with his anxious grandmother in tow pleading: «Don't reproach him, he'll be a minister one day». They looked straight over my head and exchanged a few inaudible remarks, for it was far more pressing that they respond to the honourable gentleman sitting nearby than pay even the slightest attention to the bespectacled young upstart who had just walked into the room.

The UAPI had just 18 million soms on its books, and it was time to pay the wages. How were we going to manage it? I summoned the chief financial officer and asked what we were going to do. Where's the money? How on Earth is this even possible?

«Don't worry, Komil Ismoilovich, Typography will just transfer us 2% of the turnover and we'll pay them right away» – he said.

I asked him to explain how it all worked in more detail, and what I heard grabbed my attention. As you may have well guessed, all of those various organisations were subsidiaries of the UAPI. That means that, logically, they should have been transferring their dues to head office without a murmur. But they never did. Each month before paying the employee salaries, our CFO would go through the ritual of asking them for the money: «Please transfer your share of the wage bill!» to which they would always send the same arrogant reply: «All right, we'll send it. You'll get it as soon as we have a moment». Then, he would say to me: «Komil Ismoilovich, I'll talk them round, it's always worked before». I mean, they're all eager to impress, and if their superiors ask them to, they'll transfer the money. Five publishing houses: Uzbekistan, O’qituvchi, Gafur Gulom, Chulpon, and National Encyclopedia of Uzbekistan.

«That simply isn't good enough», I said.

«Oh, but Komil Ismoilovich, they're such big fish… There's really no need, don't trouble yourself with it, I'll straighten everything out myself».

The Chief Financial Officer, having believed for years that asking subordinate organisations for money was just part of the natural order of things, had resolved to shelter me from all such unpleasantness.

I called a large general meeting and invited the managers of all of UAPI subsidiaries. The director of the Alisher Navoi National Library said that he was a bit busy that day…«so if you don't mind, Komiljon, I'll come and see you later on my own. Okay?»

I arrived on time and sat in my ministerial seat. The rest came in and out as if I wasn't even there, showing nothing but total and utter disregard for me. I remained seated, waiting patiently. Then, I couldn't control myself anymore:

«Ladies and gentlemen, please sit down and let us get started. Show a little respect!»

They took their seats. Each had a sullen look on their face and was staring stonily at me. I suppose that's what I get for interrupting their chit-chat. I drew everyone's attention to the director of publishing giant Uzbekistan.

«Please tell me about your work».

To which he responded haughtily:

«If I were to tell you everything, we'd be here till tomorrow…»

«So let it be» – I said, «Now begin».

Instilling order was more difficult than talking about it now. I started by writing a letter to all the tenants in the name of the UAPI director with the following instruction: «I hereby request that you vacate the leased premises at the earliest possible opportunity».

The way the lease worked was fairly simple – an absolute pittance was paid into the Agency's account, mere kopeks, the rest being paid in cash. I did a rough calculation of the amount in question. No less than fifty thousand dollars a month. Where all that money had gone, I had no idea. That's precisely why nobody gave a damn about whether they paid head office or not. And it also explained why the building was a shambolic, crumbling mess.

I had no personal need of that money, which, of course, came as rather a surprise to my staff. They naturally knew that I was a businessman and had money of my own, but the generally held belief was that no one can ever have too much.

As if by clockwork, I started getting calls pleading for me to spare this or that organisation. Nobody wanted to leave; they were all trying to put pressure on the new director with calls from upstairs, from various ministers and other executives. One Tanzila Kamalovna2, then President of the Women's Committee, came in person to ask me to hold off a short while, as they were currently engaged in the construction of a new building and making preparations to transfer operations there. I couldn't refuse her, but when it came to the other lessees, I didn't budge an inch.

I held my ground. The building was ours, and I needed to make it fit for the people working there. We closed the internal courtyard, removed tons of waste and rubbish, renovated all the offices, lounges and corridors. Do I really need to say who paid for it all? The entire cost of the renovation was borne by my own family business, and we were far from finished yet.

I remember meeting First Deputy Prime Minister Ochilboy Jumaniyozovich Ramatov3 at an event, where he asked me what I was doing these days. I told him that I was heading up the UAPI.

«Remind me what organisation that is again?» – asked Ramatov.

It transpired that the UAPI was such an inconspicuous and somnolent organisation that even the First Deputy Prime Minister couldn't remember it off hand. The Agency's management was almost never called to meetings of the Cabinet of Ministers. The director only knew the editors of the newspapers whom they regularly sent chain e-mails instructing them to retract this or redact that. Indeed, the only time Mr. Tangriev4 enjoyed any measure of fame was after a certain publication by Uzbekistan Publishing House in which he pledged to put the screws on any journalist who failed to observe the standards of fellow publishing house Manaviyat – the concept of intellectual and spiritual value (as he imagined it, of course).

Naturally, renovating the building wasn't his chief concern. The most important thing for him was imposing his authority as director. And what do you need to impose your authority? Just waving your ministerial h2 in every subordinate's face and demanding respect won't cut it. You have to follow the rules of the art of war. First, you have to find out who the real top dog is, the person with genuine clout and influence, the one everyone takes their lead from…and then neutralise them.

The very next day I set them all a lengthy skills test and sacked everyone who failed or refused to take it. Next, external factors required me to relieve Hurshid Mamatov of his position as Director of the Monitoring Centre. Well, his entire team actually.